I have just returned from the 2024 Philip K. Dick Festival in Fort Morgan, Colorado, an intimate and enlightening series of presentations, discussions, and visits. Fort Morgan is about 6.5 hours from where I live in Santa Fe, NM, so I took Michael Caine – not the actor, but that’s the secret name of my car – on a road trip. Jonathan Lethem was the keynote speaker, and Stephen Graham Jones was also an excellent guest panelist, and generous late-night bar companion. But I want to talk about an irony that occurred and that has stayed with me. As I write, this was 2 days ago, on Saturday, June 15th.

In the morning, at Morgan Community College, Philip K. Dick scholar David Gill gave a presentation which lingered on what has always been, for me, the most important passage of Dick’s Exegesis. I have long planned to write something more substantial on it, but have not managed to do so, yet. It occurs late in the Exegesis, and this is the passage:

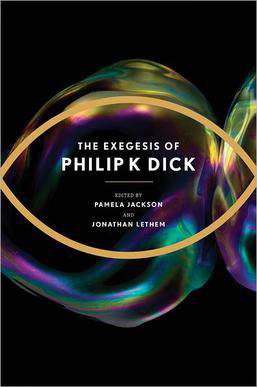

Why am I so joyful? I am celebrating a victory and can now stop work – finally – and relax. Why? Because I did my job and I know it. What was the job? To get the third dispensation in print, and I did so in Androids – I need do nothing else in my life. The Tagore vision: the Godhead expanding into the ecosystem (animal kingdom). – The Exegesis of Philip K. Dick, edited by Pamela Jackson and Jonathan Lethem, Houghton Mifflin, 2011, 827.

For readers unfamiliar with Dick’s massive, gnostic investigation, the point here is that the precession/procession of the novel referenced above – Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? (1968) – and its Hollywood adaptation as Blade Runner (1982) represented the most complete transmission of his ecological message. Relationships between the human animal, the nonhuman animal, and android or artificial life are vital to Dick’s sense of the transcendent versus the pathological. Readers will recognize this in his fiction.

Cruelty to animals has been understood as a predictor of psychopathy since the early- to mid-1960s. John M. Macdonald, a psychiatrist at the University of Colorado and Associate Director of Inpatient Services at Colorado Psychiatric Hospital, had correlated childhood cruelty to animals, fire-starting, and enuresis (bedwetting) with later homicidal violence – this became known as the Macdonald Triad; attentive readers will have noted the Colorado constellation with Philip K. Dick.

The irregular Philip K. Dick Festival has been held in Fort Morgan, CO, because Dick’s ashes are buried there, in Riverside Cemetery. Dick died in March 1982, at 53 years old. He shares a plot with his twin sister Jane who died in infancy. At the time of her death, her surviving brother’s name was pre-inscribed on her/their gravestone. Their twin birth and twin burial was assured, and their relationship is the subject of a great deal of fine analysis, not least in Laurence A. Rickels’ I Think I Am: Philip K. Dick. Of the gravesite, more later.

As David Gill made his presentation and discussed the passage from the Exegesis, I was sitting in the back row with my friends and colleagues David Agranoff and D. Harlan Wilson. Agranoff made a polite and pointed interjection to the effect that for all of the ecological consciousness and messaging in effect in the room, he and I were the only vegans present and that Dick was unable to follow through on his Kindred (Dick’s middle name) relationship with the suffering animal kingdom (which he associated with the sufferings of Christ) by ceasing to consume and exploit animals. Indeed, if Dick’s message in the Exegesis was to be important at all, then divestment from animal slaughter and exploitation should be a minimum requirement. Agranoff said, yes, we have heard all of the excuses as to why this is ‘so hard’ for people, when it has never been easier and more necessary in human history. The related question of human-animal-machine consent had arisen when Gill described the varying depictions of human-android intercourse in Do Androids Dream… and Blade Runner. I won’t cover it in detail here, except to say that I made a point regarding the nature of the ‘it,’ re. sex with androids as it is discussed in the novel between the psychopath Phil Resch and the ambivalent bounty hunter Rick Deckard, and how this plays out on screen in Blade Runner. I constellated a point on the nonconsensual impregnation/rape of cows by the dairy industry and our nonconsensual relationship with AI. So, Agranoff made his point, and I made mine. A little later, we went to lunch. The carnivores carnivored, etc. All right. This the set-up to the irony that has been with me since then.

That evening, as a storm threatened to encroach with lightning and heavy rain, we were outside listening to a brilliant 2-hour elucidation by Jonathan Lethem. In retrospect, and respectfully, I think that even Lethem might have missed a trick when – near the conclusion of his discussion of Dick – he made an analogy between Dick’s vision of a death- or tomb-world and campus protesters witnessing the ‘death world’ emerging from images of Gaza on their smartphones. I understand his reasoning, but I think the point might be better made that the death world Dick had come to, but not acted upon, concerned “the ecosystem (animal kingdom)” or the holocaust in excess of 80 billion land animals for human consumption every single year. This is a holocaust far worse than Gaza.

It was raining heavily as Agranoff, Wilson, and I made our way to Riverside Cemetery in Wilson’s Jeep. The rain gave way to a gray-gold sky. The sun would set in an hour. We searched between the stones in vain, until I remembered that Wilson had a photograph of himself at the grave from an earlier visit and we used that, scanning its background details, to orient ourselves and find the site. On our way, I marked the irony that graves in the vicinity of Dick’s pre-assigned plot were marked with the names of his some of his characters: Mercer, Archer, Frick… We are not quite at the irony that urges this writing, however.

At the grave, we were joined by friends and colleagues. We faced west over the iconic stone, and over the others of the Dick family arrayed to our left. It was a beautiful evening. I took pictures for Tom Scholte, an actor (The X Files, etc!) and Professor at the University of British Columbia. I liked Tom instantly. He photographed me. We stood together and Tom remarked on the smell of manure drifting over the plot. I said, “I bet that’s a ‘processing’ plant.” And here we come to the irony that has haunted me. Although I could not have said certainly at the time, what I know today, 2 days later on returning home, is that yes, Philip K. Dick’s grave lies under the pall of a slaughterhouse. It is the euphemistically-named Cargill Protein Processing Plant (formerly Cargill Meat Solutions – solutions to what, one must ask?) on E. Burlington Avenue. Close by that, you can find Leprino Foods which, according to its website, “converts 2.3 million pounds of milk into cheese every day.”

You cannot tell from our photographs from that evening, but the smells of shit, fear, and death pour over Philip K. Dick’s grave. If his words in the Exegesis are meaningful, and if he were (as he felt, and we must feel ourselves at different times) ‘living in a Philip K. Dick novel,’ something of his consciousness would be caught in the half-life of the grave, horrified at the proximity of the slaughterhouse, perhaps hearing the agonies of the animals through the soil of the tomb world, and the nonconsensual exploitation of so many others of the animal kingdom hard by the Riverside Cemetery.

Thank you for reading, and I hope this gives you some ideas.

— James Reich